Virtual

Humans

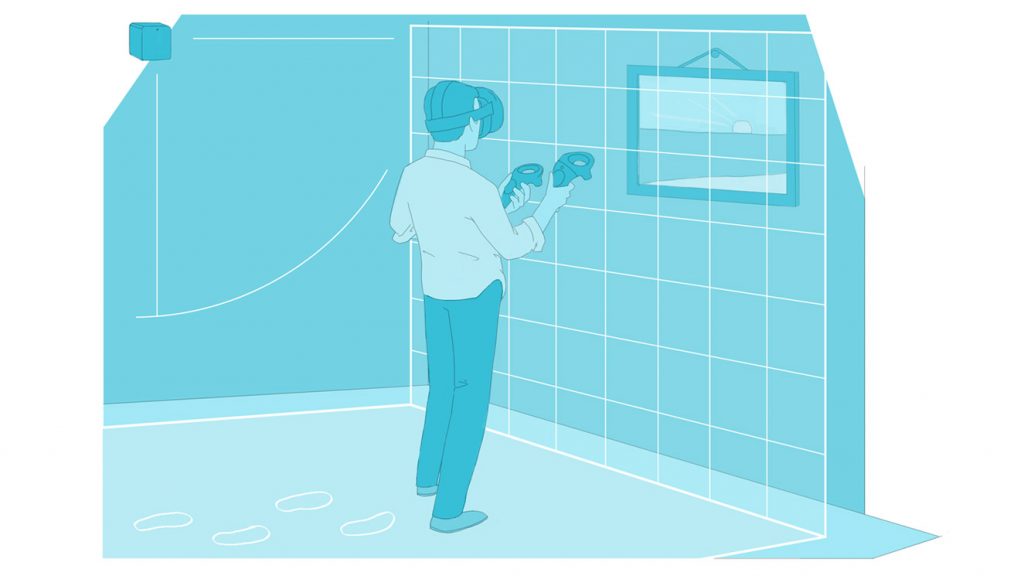

Adding to its flotsam of humans, animals, plants, objects, buildings, trash and landfill waste is now a vast depository of virtual things. These virtual things have no physicality or materiality. They are objects that are essentially computational data which have to be processed through computer software and can only be seen via a computational device such as a laptop or a smartphone. They are created and subsist entirely in digital form.

Yet they fill our world.

Myriad virtual objects from exploding barrels to customized costumes are created and cherished in videogame and virtual worlds.

Virtual currencies, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum tokens, are deployed for payment.

Virtual art objects fill virtual galleries, all made and presented in digital spaces.

Virtual avatars populate videogame and virtual worlds, socializing with each other and completing missions.

Virtual correspondences such as emails and online bills fill gazilions of virtual inboxes everyday.

The virtual sometimes crosses with the actual, such as where a piece of virtual art or videogame object is sold in the actual world and paid for with fiat money.

The New Virtuality thus also points to this thriving and replete world of virtual things. Digital objects made up only of bits and bytes, yet vitally creative and self-expressive. Computer files that have no physical form, but are able to move millions of dollars as fiat payment. Immaterial things that are nonetheless real: acquired, they are valued and treasured; lost, they are mourned and missed.

Into this world, then, enter virtual humans.

II.

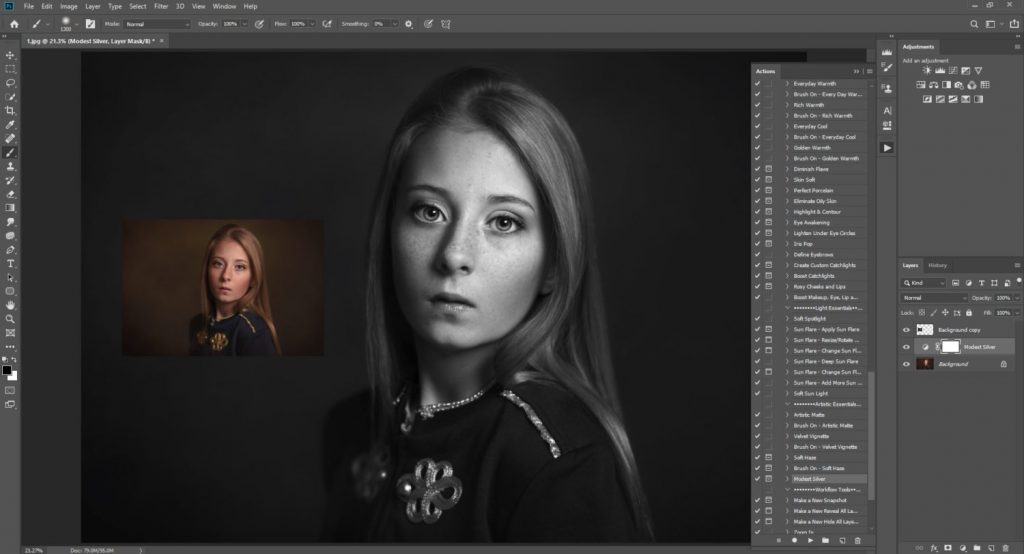

Like the virtual object, the virtual human has no physical counterpart. The virtual human is an audiovisual representation of a person, modelled and rendered entirely through computer software, and eventually appearing on screens. They are realistic in appearance, movement and sound. But they do not exist in actual reality.

For instance, Shudu Gram graces numerous magazine cover pages as a supermodel.

The media is awash with photographs of her sashaying down fashion runways. She appears as a black woman with a closely shaven head, striking lips, and the fashion model’s long and sleek body. But Gram is completely computer-generated. She has no physical manifestation beyond her myriad digital images.

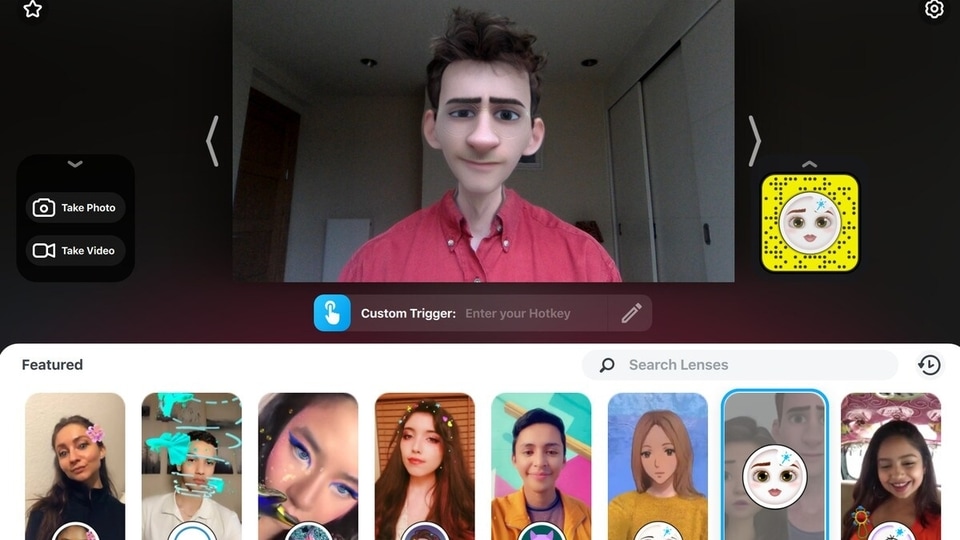

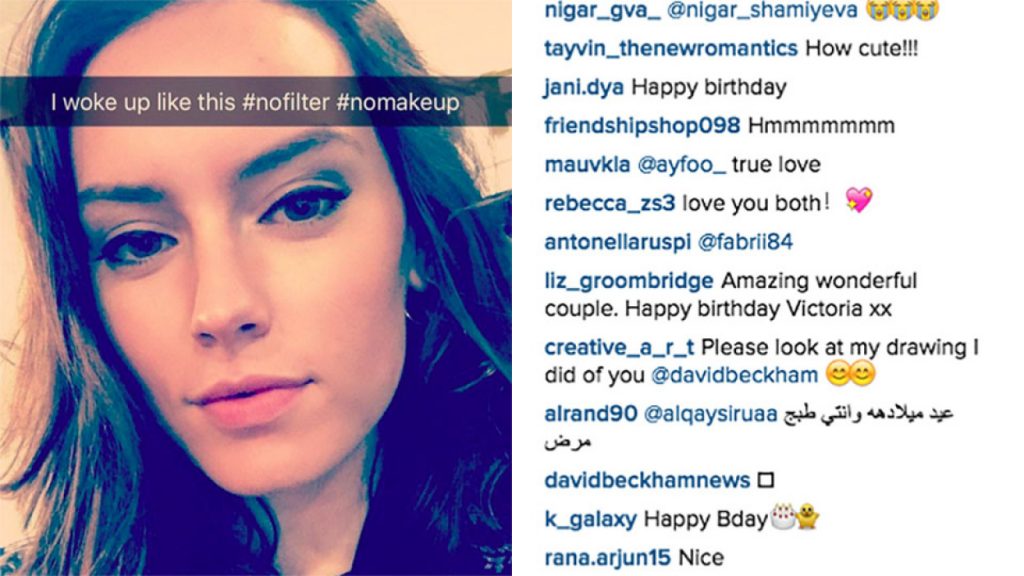

The virtual human circulates most abundantly in the worlds whose raison d’etre is to facilitate virtual circulation – social media. In particular, the virtual human reigns on photograph and video platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, where appearances rule supreme. And the virtual human, above everything else, is all about appearances.

One example of the virtual human on social media is Lil Miquela, a “Spanish, Brazilian, American” 19-year-old. Miquela is a virtual influencer with active accounts on major social media platforms, including Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram. On the last alone, “she” has amassed over 3.1 million followers to date.

Images and videos of Miquela are proliferant with updates on her life and relationships, while also promoting brands such as Calvin Klein and Prada.

Miquela looks, sounds and moves like a real person. Her virtual life is sparkling, engaging and believable. Yet she is created entirely out of computer software and human imagination. There is no Miquela in the actual world.

The virtual human need not even be made by human creators. Today, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning draw from huge datasets of photographs of actual people to create fake portraits of virtual humans.

The website ThisPersonDoesNotExist.com produces an online gallery of photographs of humans all generated by computer algorithms. While not endowed with the virtual existence of Miquela or Shudu Gram as influencers and models, each photograph nonetheless presents a realistic-looking human. But, of course, the subject is entirely virtual. They literally Do Not Exist (in actual reality).

III.

Paradoxical as it sounds, the virtual human need not always appear as a human.

The Japanese chart-topping pop star, Hatsune Miku, is a virtual performer created entirely from software in 2007. She “sings” via a software voicebank, and typically appears “live” onstage as a 3D animated projection. She is visible as a young girl styled and dressed as a character out of a manga comic. Her distinctive features are her two long “turquoise blue” twintails.

Her live concerts are large sold-out events. She even “interacts” with actual actors to advertise high-profile brands such as Toyota. Through her myriad appearances, she appears not as a human, but an animated manga character – and that is precisely the point. Her popularity stems from her manga-ish virtuality. She is engaging precisely because she is a virtual character – slightly alien, and not quite of the human world.

Similarly, in October 2021, China debuted “2060″, a variety show which features animated computer-generated characters in a live television studio.

The characters compete for audience votes and judges’ endorsement with their dance and singing performances. Heavily aestheticised in the style of fantasy manga, the virtual characters perform, interact onstage with each other and with the studio judges in real-time.

On June 3, 2022, Zhejiang Satellite TV and Tencent Interactive Entertainment Zhiji debuted the virtual performer, Gu Xiaoyu, onstage in their television studio performing a duet with Taiwanese singer Angela Chang, an actual performer.

Created with simulation and motion capture data, and rendered on Unreal Engine, Gu appeared in traditional Song dynasty dress and styling.

As with Miku, the point of these characters is to showcase their virtuality as characters of manga or historical style, and to celebrate their vitality as virtual characters who can meet and interact with actual humans in real-time onstage and in the television studio. Their virtuality – in all their cartoon-ish, manga-style glory – is feted, admired, acclaimed and, above all, accepted as live entertainment. This is also The New Virtuality – the hunger for another kind of real.

IV.

The virtual human can be lifelike, such as in the style of Miquela or Shudu Gram. Or they can be cartoon-ish, as with Hatsune Miku or Gu Xiaoyu. Both these categories of virtual humans have no referent in terms of an actual human. Which brings us to the class of virtual humans who do.

Here, the virtual human shares shades of existence with the actual human.

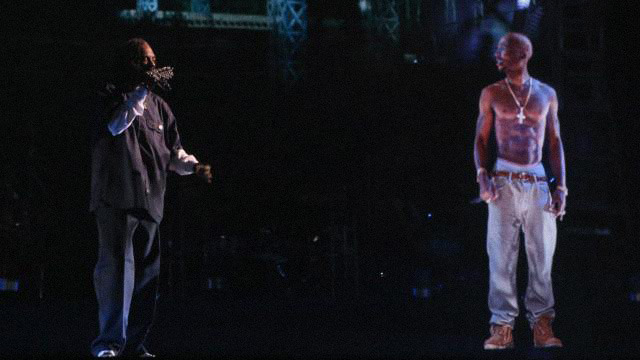

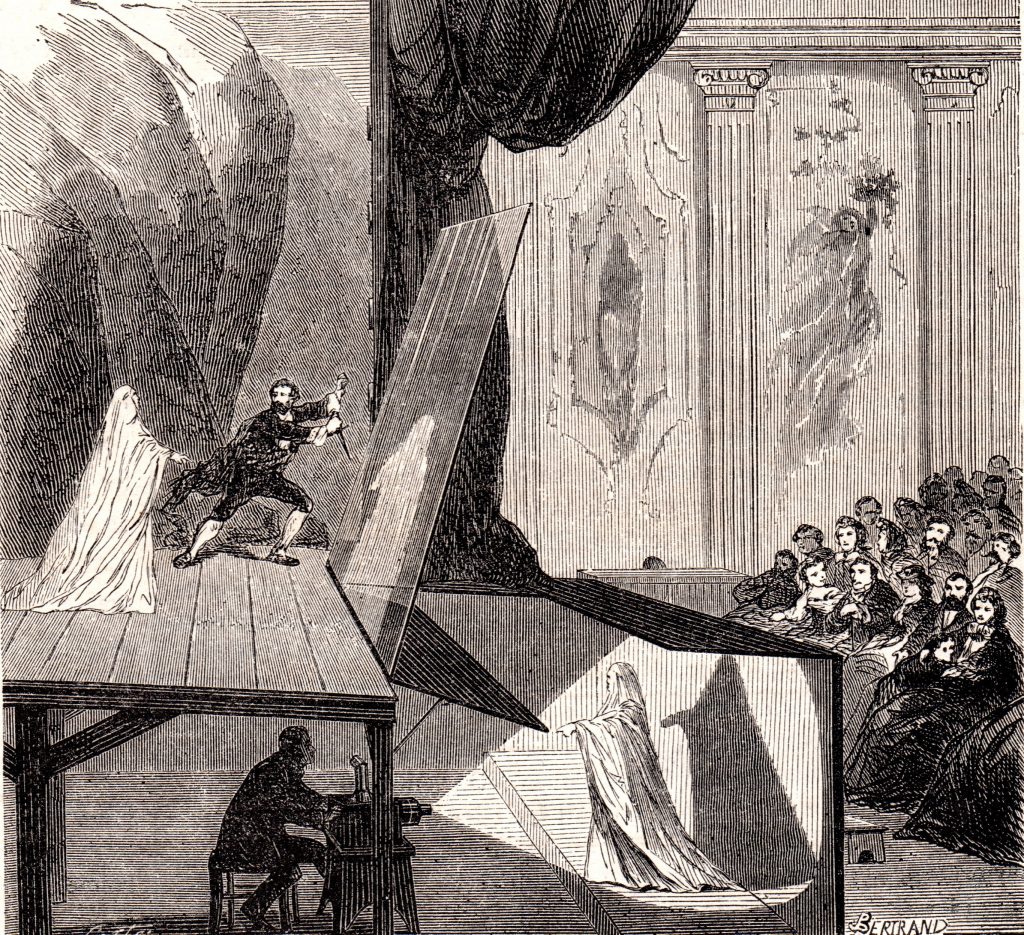

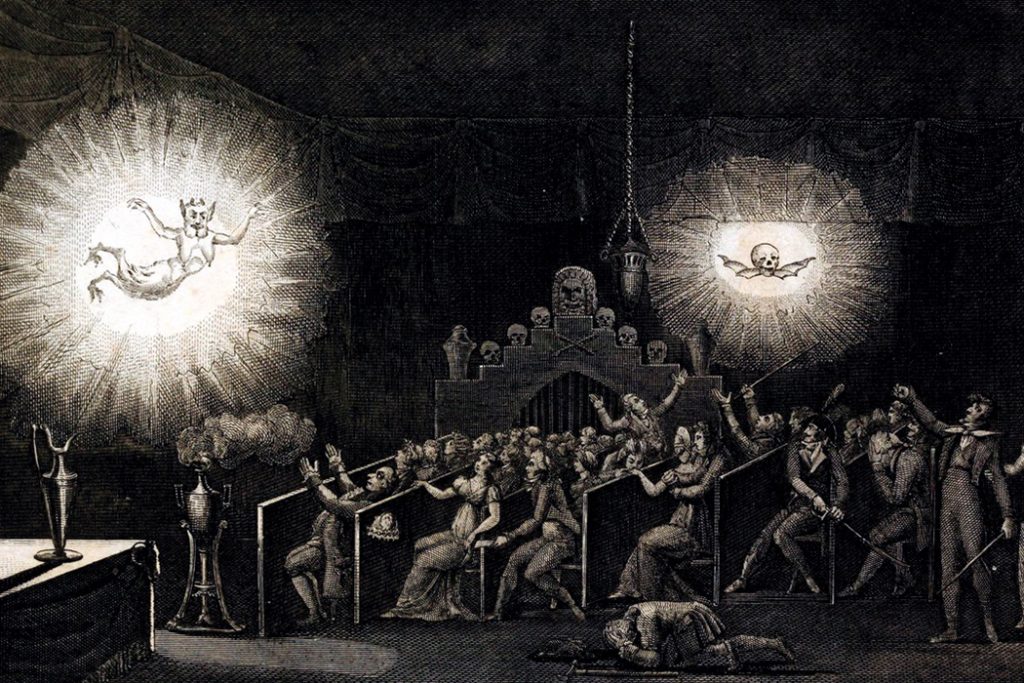

One instance is how a virtual human appears as the ghost from a dead human, the latter “resurrected” to appear before the living with life-like realism. The Phantasmagoria shows of the late eighteenth and nineteenth century presented historical (and dead) figures as profitable entertainment in its day.

The advent of the Pepper’s Ghost projection technique, patented by the two English engineers John Henry Pepper and Henry Dircks in 1863, enabled images of objects or people to appear mid-air onstage, and prompted a slew of “ghost shows” across London and Europe.

In contemporary times, the dead continue to appear in anachronistic ways, such as appearing in advertisements produced long after they had died.

Numerous dead artistes have been “resurrected” as virtual performers in so-called concerts before live audiences. Projected onstage with live backup bands, dancers or the occasional star with whom to duet, these resurrected and virtual performers have included Tupac Shakur (1971-1996) at Coachella in 2012; Teresa Teng (1953-1995) at Jay Chou’s Taipei concert in 2013; and Michael Jackson (1958-2009) at the Billboard Music Awards in 2014.

Concert tours have been made of Maria Callas (1923-1977) in 2018; Buddy Holly (1936-1959) and Roy Orbison (1936-1988) in 2019; and Whitney Houston (1963-2012) in 2020.

V.

Those shared shades of existence are becoming increasingly fuzzier. The dead at least lie in a different realm from the living (if with some ambiguity vis-à-vis, for example, brain death). A somewhat distinct threshold separates the dead from the living.

The latest virtual humans appear not as ghosts from the dead, but apparitions from the past.

On May 27, 2022, the Swedish pop group, ABBA, launched their long awaited reunion concert, ABBA Voyage. The twist: ABBA Voyage does not present the group reunited as its members are today, all well into their 70s.

Rather, the show features highly realistic computer-generated (CG) 3D animations of the ABBA members – dubbed “ABBA-tars” – appearing as they had looked in ABBA’s days of super stardom in the 1970s.

Animators and visual effects artists from the special effects firm, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), modelled, animated and rendered the ABBA-tars using negatives, footage and TV appearances of ABBA in the past. They also motion captured body movements and facial expressions of both present-day ABBA members and body doubles, using the mocap data for increased realism.

The “concert” of ABBA Voyage, then, consists of the ABBA-tars presented on a huge 65 million-pixel screen which spanned the stage. Backed by a 10-piece live band and enhanced with sophisticated surround sound and lighting effects such as laser pulses and descending ropes of light in the arena, the ABBA-tars appeared as veritable live performers on the stage, with convincing close-ups of their faces, eyes, hair and costumes. The specific aim is to immerse the audience in the presence of ABBA as they were.

The virtual human thus meets the actual human. Not across the profound threshold of death, but in real-time from one’s past in one’s present.

At Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee celebration of her 70 years in reign, the Jubilee’s live pageant paraded the Gold State Coach, built in 1762, in which the Queen rode at her coronation in 1952.

Significantly, the Queen (still alive) did not ride in the coach. Rather, her past self did as a virtual human. Created from archival footage of her coronation, the young and then-freshly crowned Queen Elizabeth II of 1952 appeared once again in 2022 as a 2-dimensional projection at the coach window which “waved” to crowds (who waved back).

The New Virtuality thus points to this plethora and diversity of virtual humans. Virtual humans who appear in every way life-like but have no referent or counterpart in relation to actual humans. But also virtual humans who appear as shades of actual humans, be that as a resurrection or as a memory. They manifest seemingly real-time interaction with other actual people. They are neither ghosts nor apparitions, neither dead nor alive, but appear in their own peculiar limbic space. The New Virtuality of virtual humans thus also ushers in the need for a new vocabulary of life and being. These new beings appear in droves before us, their virtual existence in full social, audiovisual and animated vitality. They are in our midst.

Notes

Exploding barrels: Keith Stuart, “The 11 greatest video game objects – in pictures,” July 12, 2017, The Guardian online, at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/gallery/2017/jul/12/greatest-video-game-objects-in-pictures-sonic-rings-portal-companion-cube.

Customized clothes: Abbey Parker, “Animal Crossing: New Horizons as a Platform for Virtual Fashion,” The Boar Lifestyle and The Boar Games, no date, https://warwickboar.shorthandstories.com/-animal-crossing-new-horizons-virtual-fashion/index.html

Selling virtual art: Jacob Kastrenakes, “Beeple sold an NFT for $69 million,” The Verge, March 11, 2021, online at https://www.theverge.com/2021/3/11/22325054/beeple-christies-nft-sale-cost-everydays-69-million.

Shudu Gram and Lil Miquela: Alexandre Marain (Stephanie Green trans.), “From lil Miquela to Shudu Gram: Meet the Virtual Models,” Vogue, April 5, 2019, https://www.vogue.fr/fashion/fashion-inspiration/story/from-lil-miquela-to-shudu-gram-meet-the-virtual-models/1843.

Hatsune Miku: Cara Clegg, “Is Hatsune Miku without twintails still Hatsune Miku,” SoraNews24, May 8, 2015, https://soranews24.com/2015/05/08/is-hatsune-miku-without-twintails-still-hatsune-miku/.

“2060”: Global Times, “China debuts show starring virtual characters,” Global Times, October 28, 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202110/1237554.shtml.

Gu Xiaoyu: iNews, “Cross-dimensional cooperation with Zhang Shaohan, digital person Gu Xiaoyu gave Song Yun culture a new expression,” iNews, July 24, 2022, https://inf.news/en/entertainment/75262090c110d8b53f1e6db904d09809.html.

Phantasmagoria: see Mervyn Heard, “Now You See It, Now You Don’t: The Magician and the Magic Lantern,” in Realms of Light: Uses and Perceptions of the Magic Lantern from the 17th to the 21st Century, eds. Richard Crangle, Mervyn Heard, Ine van Dooren (Exeter: The Magic Lantern Society, 2005), 16.

Pepper’s Ghost: R. McDonald Rendle, Swings and Roundabouts: A Yorkel in London (London: Chapman and Hall, 1919), 184-15.

Tupac: see “There’s a Spectre Haunting Hip-hop: Tupac Shakur, Holograms in Concert and the Future of Live Performance,” in Death and the Rock Star, eds. Catherine Strong and Barbara Lebrun (New York; Oxon: Routledge, 2015): 177-189, 179.

Teresa Teng: CGTN, “23 years on: Death can’t do Teresa Teng and her Chinese fans part,” China Daily, January 29, 2018, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201801/29/WS5a6edc6aa3106e7dcc1376ad_1.html.

ABBA Voyage: Kitty Empire, “ABBA Voyage review – a dazzling retro-futurist extravaganza,” The Guardian online, June 4, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2022/jun/04/abba-voyage-review-a-dazzling-retro-futurist-extravaganza.

Queen Elizabeth Platinum Jubilee: David Meyer, “The Queen appears as hologram in carriage before surprising crowds from balcony,” New York Post online, June 5, 2022, https://nypost.com/2022/06/05/queen-elizabeth-makes-jubilee-appearance-as-hologram/.