The

Unreal

I.

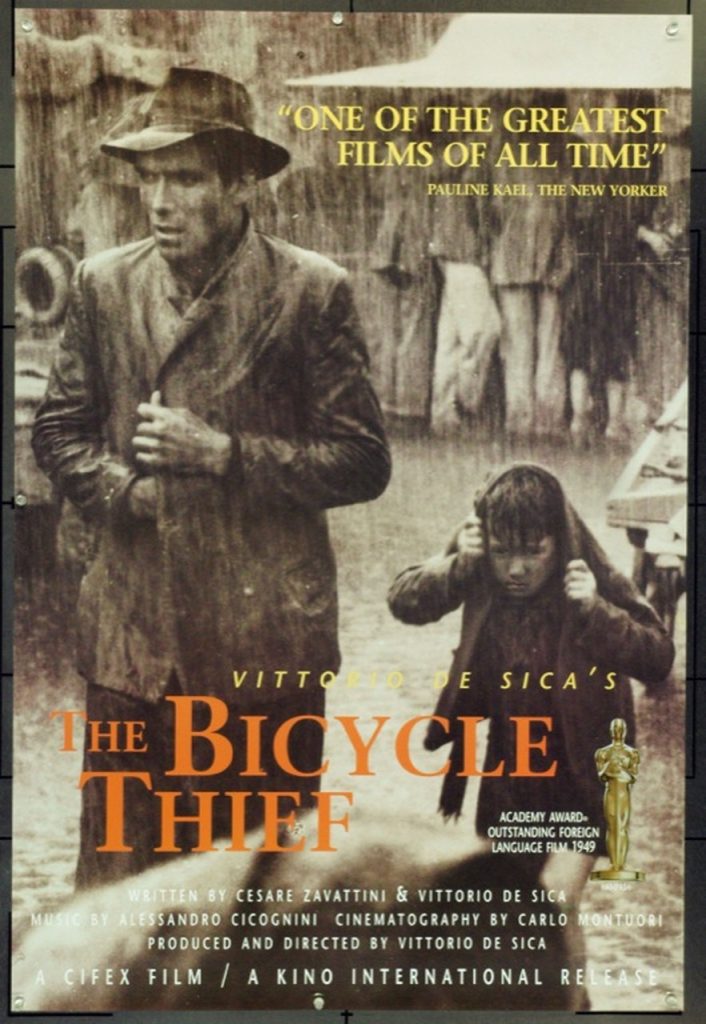

A scene. On April 1, 2013, a motley crew rocked up in a shopping centre at the Dutch town of Breda. They are a curious group – an ensemble of characters decked out in seventeenth century dress. The actors proceeded to re-enact various scenes: a thief clutching his spoils and fleeing with guards in hot pursuit. Two military figures marching into the square at the head of a cavalry. A dwarf scurrying along while shooing the crowd. A girl picking up her skirts and running after a squawking chicken.

Initially appearing as an ostensible April Fool’s joke, the performance turned out to be an ingenious publicity stunt for the 2013 re-opening of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam which had been closed for a decade-long renovation.

For the skit’s denouement, the actors assembled in the central space of the shopping centre, taking up various positions and postures. Realization soon dawned on the watching public: the actors were arranging themselves in correspondence with the characters in Rembrandt’s famous 1642 painting, De Nachtwatcht. To advertise the Rijksmuseum’s re-opening, the actors had re-created the museum’s arguably most famous painting.

Once each actor was in place, the concluding touch arrived: a rectangular construction, bearing the museum’s opening and sponsorship notices, descended from the ceiling and came to rest around the actors. The painting is framed, the spectacle contained. The unreal of the flash mob performance now made real… as an unreal painting. A virtual scene that points only to another virtual scene.

II.

This is The New Virtuality: an era of the unreal replete with images that are neither entirely fake nor entirely true.

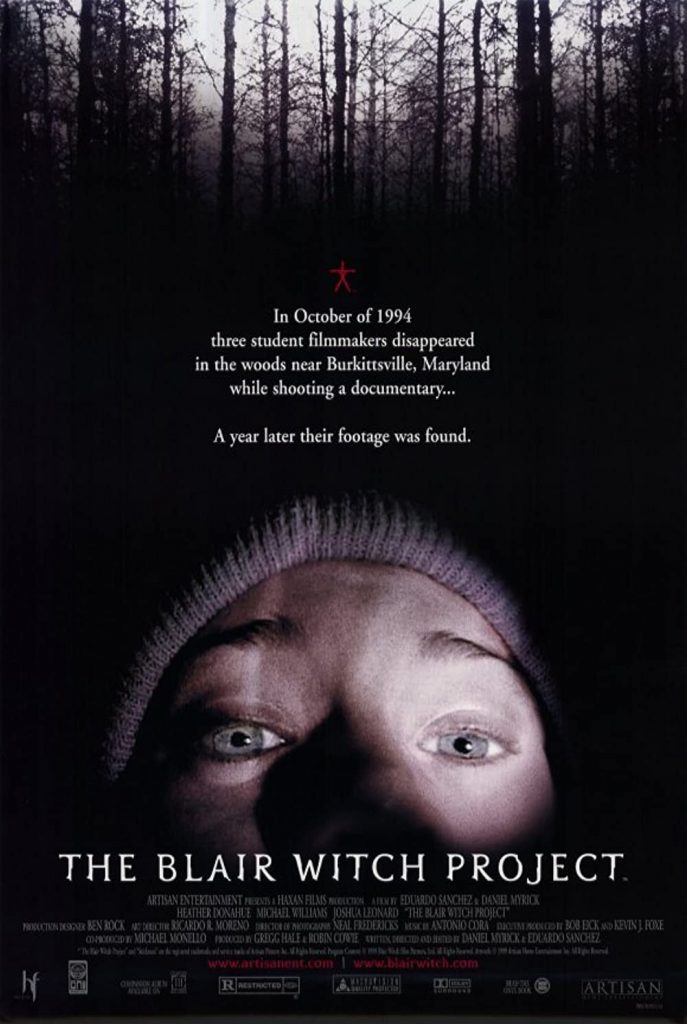

This era of images is distinct from the real of CGI and digital manipulation, whose fakery deceives and tricks.

In The New Virtuality, no one is taken in. Yet no one believes either. The New Virtuality teeters between extreme naturalism and unabashed fakery; recognizability and open alteration; realism and manifest manipulations. Neither on the pole of the real nor the unreal, The New Virtuality is off-balance and uncertain. It can only vacillate.

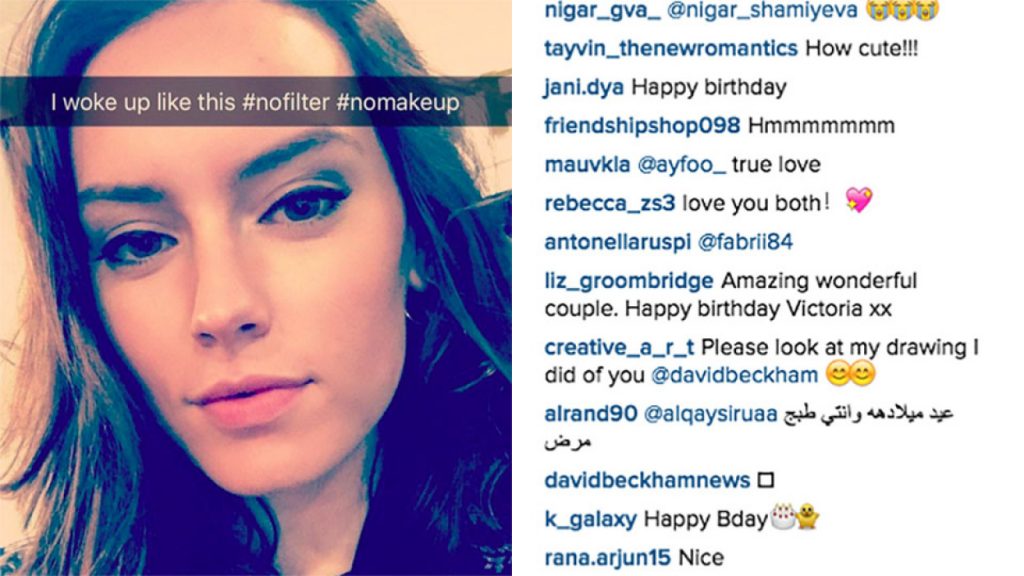

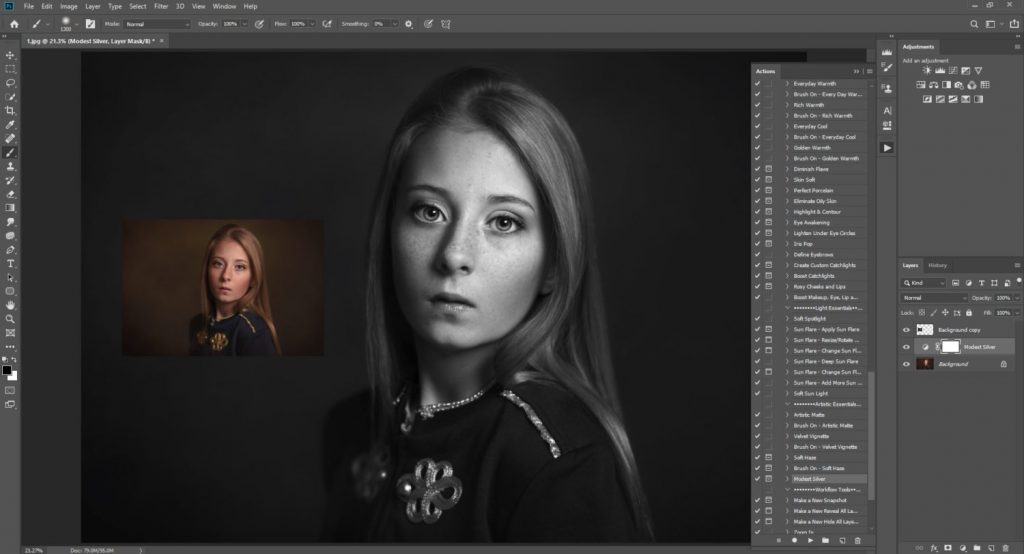

This vacillation is in all the Instagram photographs touched up with the dozens of photo filter apps available on every smartphone. The photographs look simultaneously real and unreal – a hybrid whose real is as yet ungraspable and incomprehensible; appearances which are changed and “enhanced”, yet remain recognizable. Realistically yet unrealistically perfect.

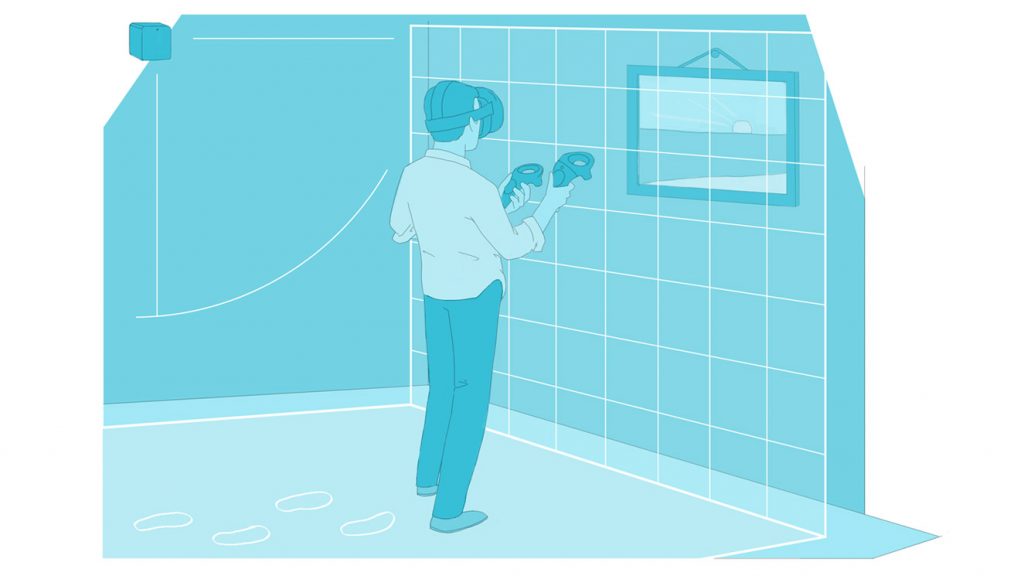

Or the vacillation in the latest manifestation of Virtual Reality (VR) as “location-based Virtual Reality” (LVR), where the user straps on a VR backpack and moves through an extensive physical space. Actual space thus corresponds with the virtual as a space, where virtual movements match actual movements.

As one reviewer describes his experience in the “Star Wars” LVR: “When I walk forward in Secrets of the Empire, I actually walk forward.” The VR headset – indicative of actual/virtual boundaries – is still over the user’s eyes. No one believes the virtual scene before them is actual. Yet as the synchronicities between the virtual and the actual edge ever closer, the scene is not unreal either.

Or the vacillation in the virtuality of teeming online life on Zoom and other video conferencing platforms, particularly as the world went into lockdown over 2020-21 in response to the Covid-19 pandemic (and continuing as workers maintain WFH (Work From Home) and remote office working).

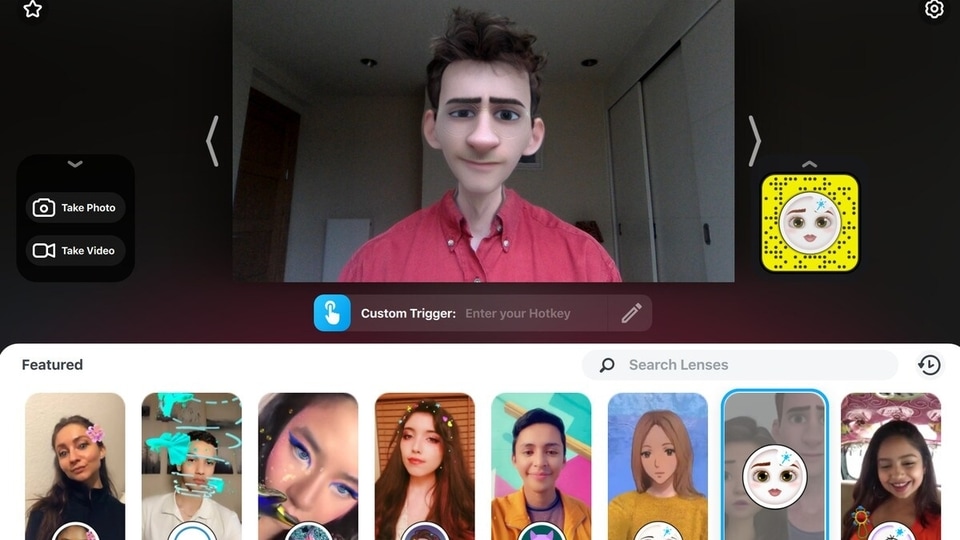

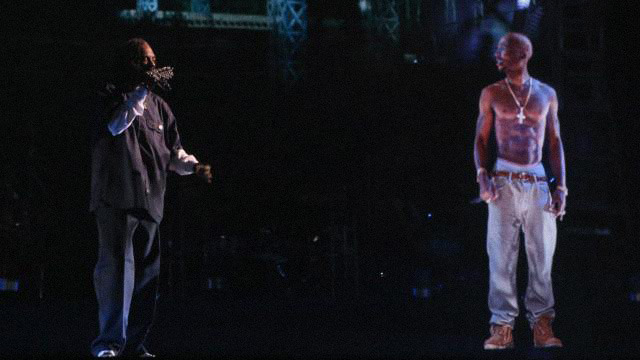

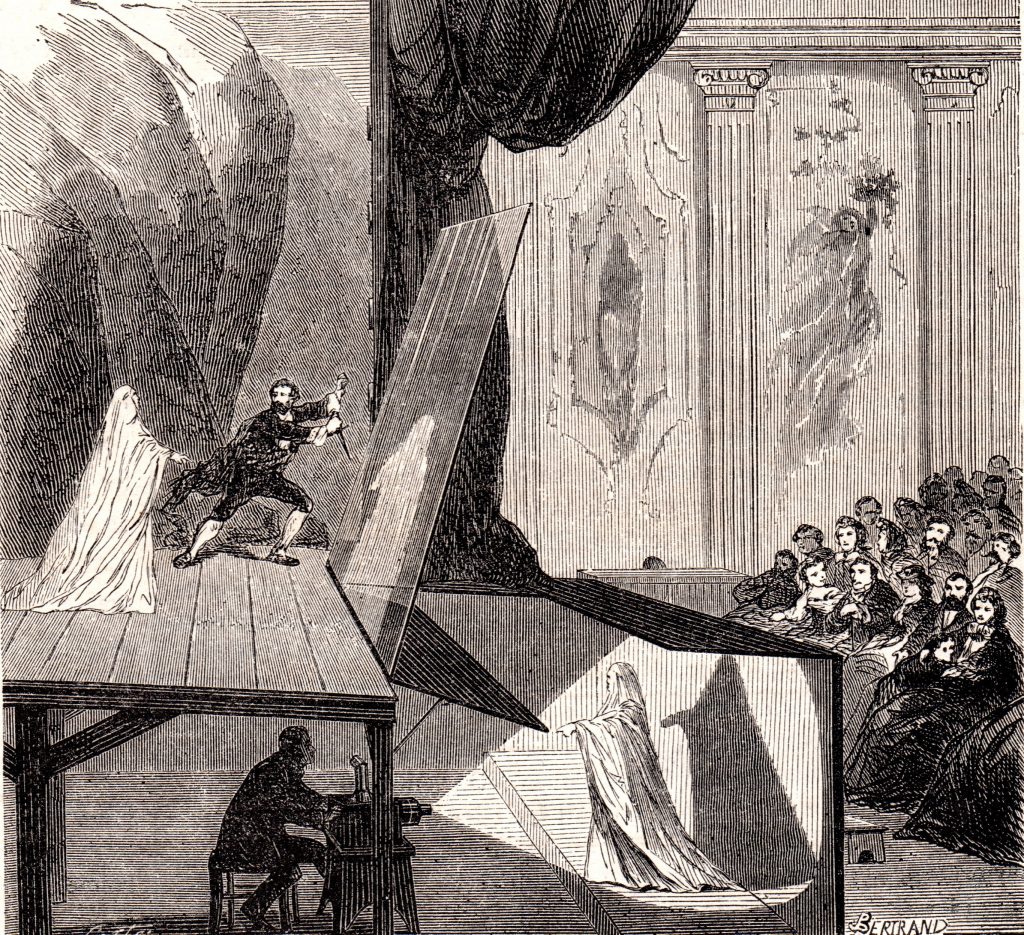

In a single pandemic-driven tectonic heave, the virtuality of webcam images become genuinely viable substitutes for living bodies at work and play. The real via the webcam readily manifests as the unreal via video enhancement in actual time; simulated backgrounds which change coherently with the user’s movements; “touch up” filters; and deepfake software. Here is the actualized cartoonization of the real in actual time; or the unreal occupying the real in real time. In due course, there will also surely be realistic real-time avatars whose virtuality completely replaces the human onscreen – the vision Meta (Facebook) plugs as the metaverse.

III.

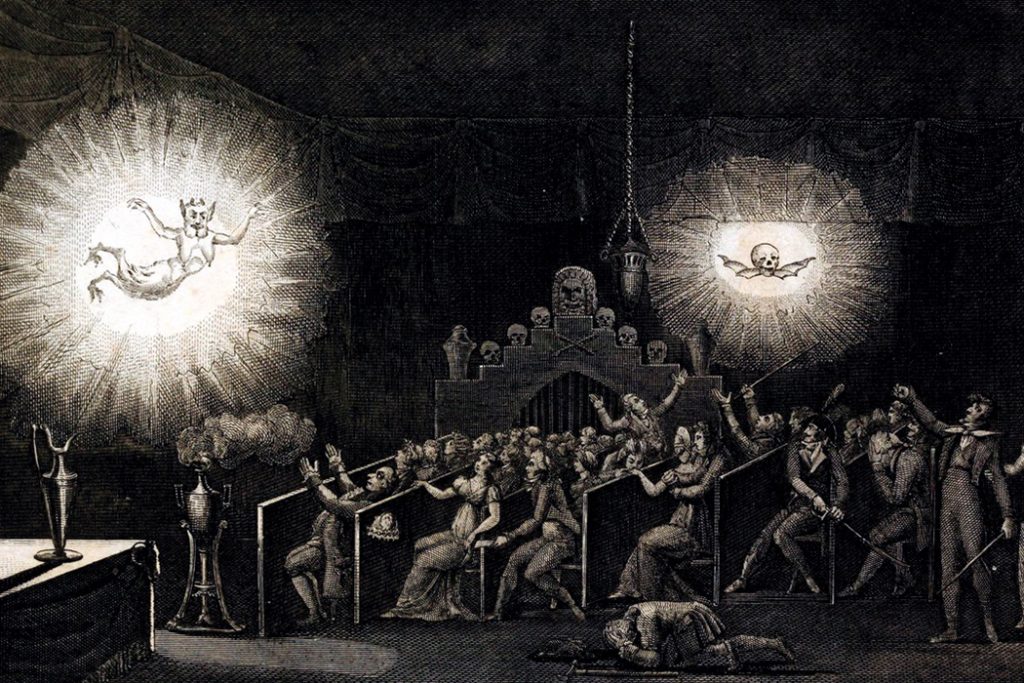

The New Virtuality thus points to a discomfort – a scandalous and impossible madness of a black hole of representability between real and unreal, the sense of this limbic space that still does not quite have a name and is completely unhistorical. A new kind of uncanny photorealism. Another creature of mutant hybridity. An endless see-sawing that abandons all the old semantic values of reality and illusion.

With this discomfort also lies a sense of threatened collapse and hidden violence. The New Virtuality is not just the constant streams, scrolls and walls of real-yet-unreal images. It is also a veritable devouring of each other – and of ourselves – to the disappearance of ourselves, or at least some level of authenticity of ourselves. The limbic vacillations of The New Virtuality also somehow swallow all the fakery in the contemporary plethora of images and spit them out as masticated versions of ourselves, a process accelerated by the enforced migration to online existences due to Covid-19-driven lockdowns and restrictions. We are left at the mercy of this constant gorging.

This force of consumption is not quite coercive as it is mindless, not quite intimidating as a helpless thrall. But it colours the limbic real-yet-unreal space of The New Virtuality with a distinct aggression. The real/unreal of The New Virtuality is thus an all-encompassing absorption that is not the antagonism of the twentieth century’s real in its shocks of brutality, disorder and destructiveness for a kind of sought-after clarity. Rather, it is the aggression of the ceaseless ingestion of virtuality which has no material existence. It is the invasive encroachment of the virtual into real-time actuality. It is the wilful oblivion to understanding or realizing our saturation of images as a surfeit that is inevitably without any kind of satisfaction.

The New Virtuality thus signals an entirely different kind of violence. That violence is one of unfulfilled yet uncontrollable gluttony of the virtual. Of unspoken desperation at being lost in the surfeit of virtuality which seems beautiful and perfect in every way, yet shredded through with an inexpressible sense of emptiness and disorientation.

IV.

One final scene. I am at the top of the world. I stand on the observatory deck of Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world at 829.8 metres from ground to tip, on its 124th floor, 450 meters towards the sky. The elevator trip alone took three minutes.

At that height, the famous skyscrapers of the city of Dubai look like geometrical saplings (remember this is a city which boasts twelve of the world’s tallest seventy buildings). In the distance, the Arabian Desert stretches into dusty and dusky shimmers.

With a constitution happily unaffected by vertigo, I stepped right up to each window pane of the observatory deck, gazing towards the view as if at a panel of a continuous panorama painting. At that elevation and out of each large glass pane, my visual reference to the scene before me was not only godlike, but essentially virtualized. The view at that height has no spatial or dimensional relation to its reality on the ground – a reality I had only half an hour ago observed and photographed from the tourist bus at ground level before boarding the elevator. This view is alien, disorientating – it is virtual. This view contains its own order of reality.

At the same time, it is also actual: the view was right before me. It constituted my actuality. Here the boundaries have completely disappeared. Difference is neither illusion nor trick of light. Rather, this virtuality is commandeered through a bodily experience of the visual and the affective which could only make sense of this data as an unreal. This was not an image in the sense of that which tries to capture the scene, such as a camera or a painting. This was an image that was in me. This was not a virtual scene. This was The New Virtuality.

So here, perhaps, is the destination of The New Virtuality, arrived at the giddy heights of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai: not so much in any technologically new methods of representation, but in profound internalization within my body, my senses, my neural connections, in my brain as a screen. Where the virtual onscreen had always been on the outside (as in, outside of the spectator) to be captured, The New Virtuality erases the difference between spectator and actor. In its final form, The New Virtuality is to be neither a second order of the actual nor even simulacra. Those senses of the virtual maintain a distance between image and the originating referent. Rather, The New Virtuality is to be a virtuality that is internalized. Or, ingested as triangulation between media, environment and bodies. In turn, that internalization becomes the ultimate extinguishment of boundaries and difference. An extinguishment that points to new questions of where, how and in what ways do we count as being in existences now no longer simply replete with screens, but made essential and indeed possible only through them.

Notes

“Location-based Virtual Reality”: Anshel Sag, “Location-Based VR: The Next Phase of Immersive Entertainment,” Forbes online, January 4, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/moorinsights/2019/01/04/location-based-vr-the-nextphase-of-immersive-entertainment/.

Metaverse: Shirin Ghaffary, “Why you should care about Facebook’s big push into the metaverse,” Vox online, November 24, 2021, https://www.vox.com/recode/22799665/facebook-metaverse-meta-zuckerberg-oculus-vr-ar.

“My body, my senses, my neural connections”: see also Gilles Deleuze’s memorable phrase, “the brain is the screen”, first stated in a “remixed” interview with Pascal Bonitzer et al. as a response to why he chose to study philosophy through thinking about cinema. His answer:

Because “thought is molecular”: “The circuits and linkages of the brain don’t pre-exist the stimuli, corpuscles, and particles [grains] that trace them. Cinema isn’t theatre; rather, it makes bodies out of grains……Cinema… never stops tracing the circuits of the brain.” Interview originally published in Cahiers du cinéma 380 (February 1986); here as taken from Gregory Flaxman, The Brain is the Screen (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 366.